RAPHAELA ROSELLA

YOU DIDN’T TAKE AWAY MY FUTURE, YOU GAVE ME A NEW ONE

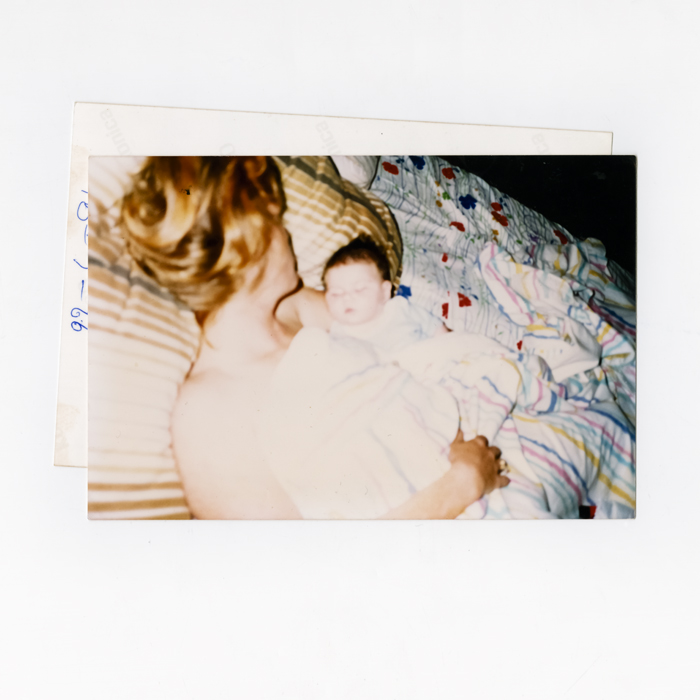

With teenage pregnancy stereotyped as a social problem, most dominant discourses do not consider the limited choices available to many young women experiencing ‘disadvantage’. As a consequence, becoming a mother at a young age can be perceived as an irrational and irresponsible choice. However, for many disadvantaged youth, becoming a parent young may not be a ‘failure of planning’, but instead a tacit response to the limited choices and opportunities available to them. Through exploring relationships between class, stigma and gender, and giving voice to young mothers through documentary storytelling, ‘You didn’t take away my future, you gave me a new one’ seeks to explore the lived experience of three young mothers; Nunjul, Tammara and Rowrow. The aim of this project is not to argue the oversimplified narratives of ‘good’ or ‘bad’ mothers. Instead, it is hoped that the project can serve as a platform to show the complexities of each woman’s lived experience, and challenge conventional views of young mothers through recognising the validity of their (often misunderstood and stigmatised) choices.

Please note: The installation of this project was presented with audio scapes of the women telling their own stories. You can view the photographs in their intended format along with the installation shots here.

Nunjul: I remember Nunjul from my childhood, she was always reserved – she didn’t talk much, and wore a patch over her lazy eye. She didn’t live with her parents; she was placed in foster care before her mother passed away. Every second week, Nunjul and her sister would stay with a family in my neighbourhood – respite care from their main foster family. For the past eight months I have been visiting Nunjul at her home in Tweed Heads, New South Wales. She recently turned 18, and her son BJ is two years old. In November 2011 The Department of Community Services (DOCS) removed BJ from Nunjul’s custody because she was in a violent relationship with his father. To end the relationship, Nunjul made the decision to move away from her hometown. Rather than being supported in the decision to leave an abusive and unhealthy environment, she describes DOCS reaction to her move as an ‘inconvenience’ for the department.

Tammara: I went to school with Tammara. Her mum was strict, and my friends bullied her because of her frizzy hair. She left high school early, and had her first baby, followed by a second soon after. She wasn’t in a good place; depression, drugs, alcohol and a turbulent relationship resulted in the removal of her first two children. She admits at that stage in her life, she had given up. Twenty months ago I started visiting Tammara during her third pregnancy with her new partner. She was a part of my previous project We met a little early, but I get to love you longer (20110. Although Tammara had moved interstate, her circumstances were now even more complex. Seventeen weeks pregnant, homeless, and in a relationship with a partner waiting to be sentenced by the court, I wondered whether this baby would be the catalyst for change in her life. Despite her transient circumstances I continued to visit Tammara and her family, and we decided to continue telling her story. One year on, we recently celebrated Tamika’s first birthday, and one year of Tammara being clean from drugs.

Rowrow: Rowrow is from Moree, but we met at a hotel in Armidale, New South Wales. A community organisation called Beyond Empathy brought us together for a project – we were both participants. Rowrow had a life like many youth involved with Beyond Empathy; experiencing reoccurring hardship, but was motivated to live a different life. A few years ago I heard she had become a mother, and that she had ‘changed’. I started visiting Rowrow and her family seven months ago. Rowrow’s community experiences entrenched poverty, racism, violence, drug and alcohol misuse, and a range of other barriers to health and wellbeing. Although Rowrow has a strong sense of belonging and connection to her indigenous culture and community, she tries to avoid many of the issues her community faces in order to provide a better future for her children. As a consequence, she runs the risk of upsetting family members and friends for being distant and reserved – something that is perceived as culturally unacceptable in her community. Nunjul, Tammara and Rowrow have all removed themselves from their environment in an attempt to provide a better life for their children. However, in all cases, with this removal has come social isolation (physical and psychological) and loss of community. This isolation was not a symptom of childbirth but a consequence, as they all attempted to fracture the cyclical nature of their individual disadvantages.

BIOGRAPHY

Raphaela Rosella (1988) is an Australian documentary storyteller from Nimbin, Australia. Raphaela is currently issue editor of The Australian Photojournalist, a non-profit publication dedicated to giving voice, celebrating the human condition and casting a critical eye on journalism and mass media practices. Raphaela works closely with organisations, Slippry Sirkus and Beyond Empathy across communities facing recurring hardship, in a hope to use photography to influence change. She was recently awarded the FujiFilm Photographic Award, a scholarship presented to a body of work that documents aspects of the human condition and was given an honorable mention for her young mothers project entered in the FotoVisura Spotlight Grant.

Named Australia’s Top Emerging Documentary Photographer by Capture Magazine, Raphaela most recently was awarded the Qantas SOYA Photographic award where she travelled to France and attended a workshop with Magnum photographer Alessandra Sanguinetti during Les Rencontres d’Arles. Raphaela holds a Bachelor of Photography majoring in Photojournalism with first class honours and is currently based in Brisbane, Australia. In 2012 she joined Oculi. To see more of her work visit her website.